A loud clang breaks the solemn silence that fills the corridor while a metallic voice informs us that this is the fourth floor. Rushed steps of a nurse exit the elevator and disappear in one of the rooms. The sound of abnormally loud TV-sets pushes its way through the closed doors, but barely succeeds in surpassing the tic-tac of the clock on the wall. The smell of food that swirls up the stairs hints that those who are heal-thy enough will soon leave their rooms and take the elevator to the dining room.

Saoul Modiano Home for the Aged is a special home. It is managed by the Jewish Community of Thessaloniki and it is open only for Greek Jews over 65. Here lives the last generation that survived the Holocaust as adults, the last generation that speaks Ladino.

History is usually read in books, but here it is possible to feel it, here it is possible to talk to it. History is on the walls, in the old photographs and in the family pictures from Israel.

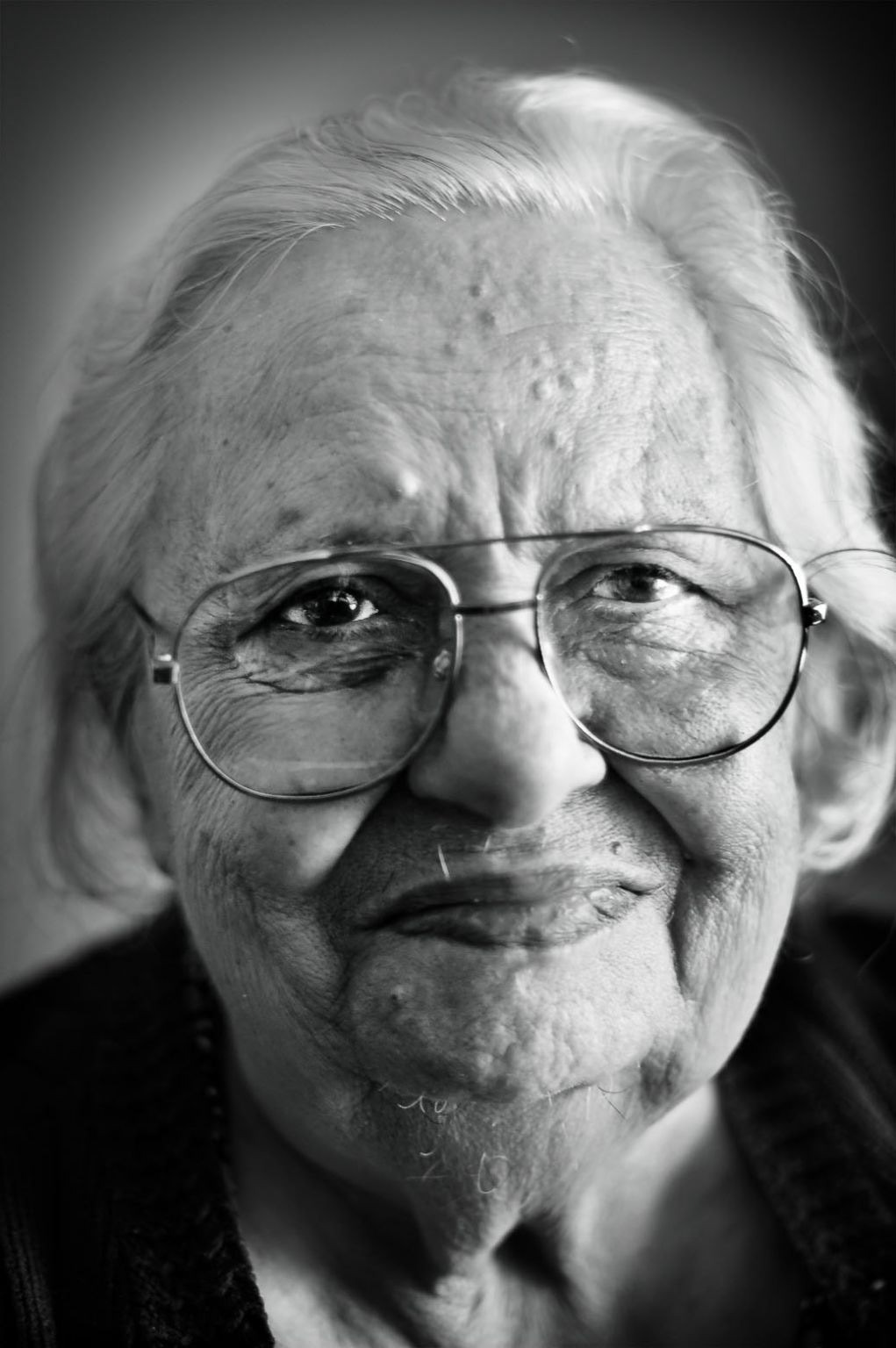

But above all, history is in the people; in the wrinkles, in the moist eyes and in the tired steps, but also in the soft ladino words, the deep gazes, and the long silences... particularly in the silences.

BACKGROUND

In 1492, around 200,000 Jews were expelled from Spain and established themselves all along the Mediterranean Sea. Their descendants still today speak this variant of Spanish (Ladino).

In April 1941, German troops marched into Thessaloniki. The freedom that the Jews of the city had enjoyed for over 2,000 years came to an abrupt end. After two years of occupation, over 45,000 Jews were transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in cattle trains. When the war was over, more than 95% of the Jewish community of Thessaloniki had been killed. Today the Jewish Community of Thessaloniki consists of 1,200 people.

BACKGROUND

In 1492, around 200,000 Jews were expelled from Spain and established themselves all along the Mediterranean Sea. Their descendants still today speak this variant of Spanish (Ladino).

In April 1941, German troops marched into Thessaloniki. The freedom that the Jews of the city had enjoyed for over 2,000 years came to an abrupt end. After two years of occupation, over 45,000 Jews were transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in cattle trains. When the war was over, more than 95% of the Jewish community of Thessaloniki had been killed. Today the Jewish Community of Thessaloniki consists of 1,200 people.

Silia Levy’s eyes moisten when she talks about the two years she spent in Auschwitz. But despite the terrible memories, she tells about a lesser-known side of the life in the concentration camp. – Some guards would yell at us when their superiors were present, but behind their back they would try to protect us as much as they could, she says pensively. After the war, she and her husband received help from the international Jewish community. – We did not have anything left. My husband began working as a craftsman, and with time we achieved a good social position.

When the war broke out, Alegra Rofel fled with her boyfriend to Athens under a false identity. Alegra survived, but her life was changed forever. – Hitler killed my whole family. Our house was destroyed, we could not even afford to buy shoes, she says. With her newborn daughter in her arms, Alegra got married after the war. She began then working as a seamstress, making “beautiful dresses”. She has now ten grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. Alegra has lived here for six years and enjoys it. – What else am I going to do?, she says with a big laugh.

Eliau Atun is from Trikala, a town 200 km southwest of Thessaloniki. When the Germans marched into the country, he went into hiding and joined the partisans to fight against the Germans. – Our neighbors helped us escape from the Germans, we pretended to be traveling salesmen.

Once the war was over, he walked for six days back home to Trikala, where the tragedy was awaiting him. – I lost ten members of my family. In 1939 I went to Thessaloniki and visited my sister, that was the last time I saw her.

Moisis Bourlas became a member of the Greek communist youths in 1935, at the age of 17. When the war broke out, he was serving in the Greek army and he was rapidly transferred to the Albanian front. When the German occupation became a fact, he joined the partisans in the mountains of Macedonia. – Those were hard times, often many days went without food nor sleep. But for him, the hard times did not end with the war. Due to his ideas, he was imprisoned in 1945. After six years he was released and emigrated to Israel, but in 1967 he had to leave the country due to the growing anticommunism. He established himself in the Soviet Union until in 1990, when he decided to move back to Thessaloniki. – I had to fight hard in order to recover my Greek nationality, but I finally managed it in 1999, he tells proudly.